You can skip all the books with this easy to follow guide.- Photo by Author

When I started with open source contributions in April 2019, I remember being scared about doing everything wrong. I didn’t want to mess up on a pull request and be branded as a noob, never able to taste the sweet success of getting an open source pull request reviewed and merged.

There were so many questions that I had to find answers to:

- What skills do I need to be able to contribute successfully?

- How do I write commit messages correctly?

- What is forking? What is upstream?

Although there were articles and tips and tricks available on the web, it was tedious to gather all the necessary information bit by bit.

After contributing to open source projects regularly for a while now and feeling comfortable with the workflow, I decided to share my knowledge with you so you don’t have to start from zero like I did.

Additionally, my motivation is to bring people who are hesitant to start with open source contributions to take the first step. More developers contributing to open source projects means better quality of code, more documentation written and faster development speed which is a benefit for all of us.

Why you should contribute to open source projects

- Improve your coding skills. Working with different code bases is a great way of getting better at coding fast. Contrary to a work environment where you might work on one project for a longer period, with open source projects you can switch to another project whenever you want and get to know various tooling and setups.

- Give back to the community. You are probably using a lot of different repositories daily for free and this is your chance to contribute as a way of thanking the project.

- Improve your prestige. You will be easier to hire with merged pull requests for well-known projects or you might even turn into a thought leader for a certain topic.

- Work with different teams. Each repository has different contributors and coding conventions that you will need to adapt to.

- Solve interesting problems. Finding solutions to complex problems can be fulfilling and a lot of fun. You are also able to choose which issues you want to work on.

If you think that you don’t have enough experience to contribute to projects with code, don’t worry. You can always help out by improving documentation, answering issues, or with the internationalization of a project until you feel ready.

Some of my contributions

To give you a bit of an overview of projects that you could be working on, here are some open source contributions that I worked on:

- sveltejs/svelte: add accessibility rule

- sindresorhus/eslint-plugin-unicorn: add lint rule

- microsoft/webtemplatestudio: improve generated angular and react code, fix e2e tests

- react-boilerplate/react-boilerplate: dependency changes and upgrades

- ethereum/ethereum-org-website: fix

setTimeoutleak, fix accessibility issue - foundry376/mailspring: add preferences options, allow cancel upgrade prompt

As you can see, my favorite areas in web development include working on code quality improvements like linting and accessibility as well as dependency upgrades.

One of the great things about open source contributions is that you get to choose whichever issue you feel like working on right now!

Contribution flow

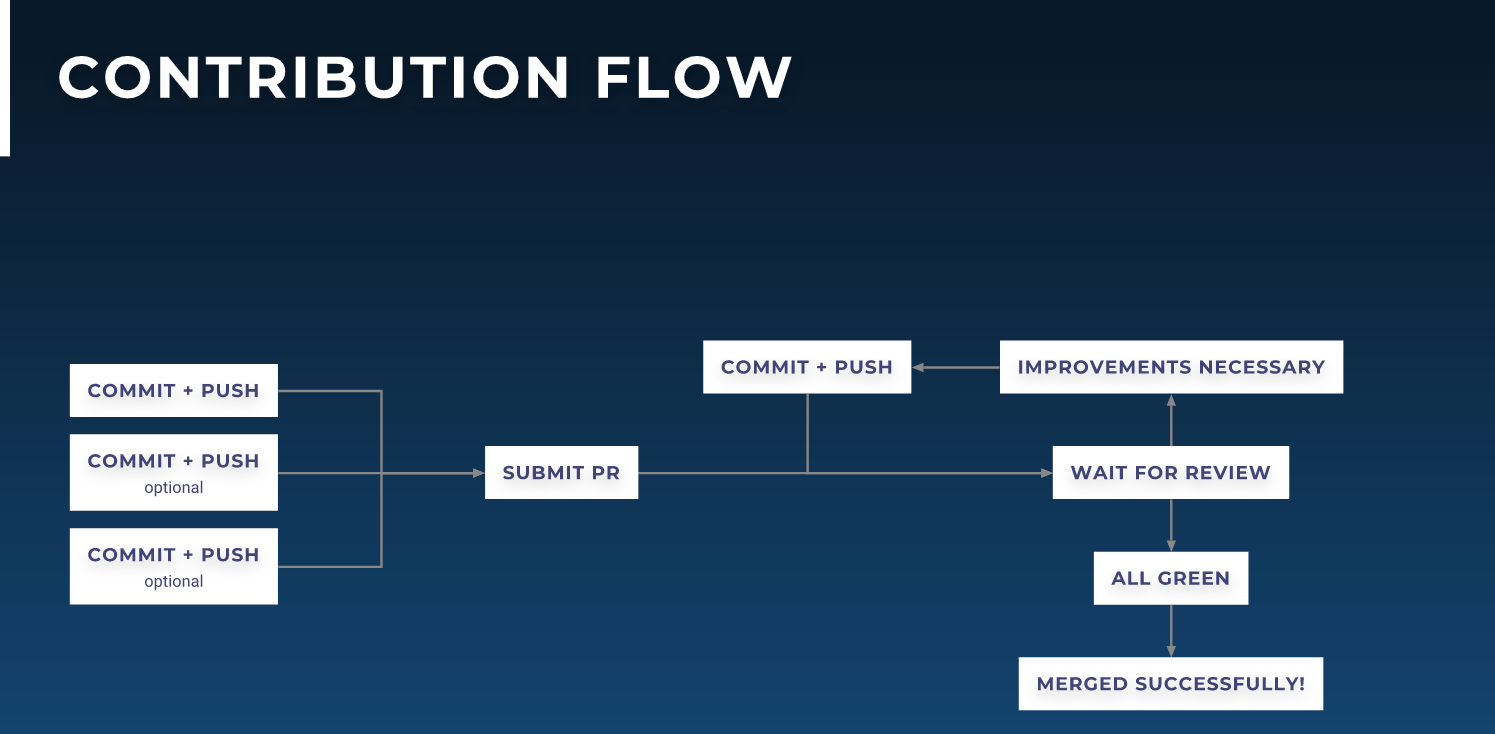

Before starting to work on open source contributions, it is essential to know how the usual workflow will look like.

A high-level overview of the step by step flow that open source contributions follow.

Although most pull requests can be created, reviewed, and merged within the same day, it is not uncommon for pull requests to take even multiple months from start to finish! I have pull requests which are open for more than a year, and they are not merged yet because the project is maintained irregularly or project focus moved away from that issue.

How to find a project to contribute to

- GitHub: there is an Explore page where GitHub recommends repositories based on your interests and previous contributions.

- Work: you are actively using a repository for a project at work. You want to fix a bug or add a feature that is necessary for your progress at work or you simply want to contribute as a way of giving back to the project.

- Contacts: you hear from co-workers or friends about cool repositories and want to be part of them too.

- Stock Market: not the most obvious way, but you could be invested in a company and want it to flourish.

Naturally, starting an open-source project yourself if you have a great idea is an option as well.

Bug bounty programs

Unfortunately, participation in most open source projects is voluntarily and therefore unpaid, but there are websites where you can find issues with monetary rewards on them:

- Issuehunt: I collected various bounties of up to $100 for issues here and the site gets updated regularly, so I highly recommend you to check it out.

- Gitcoin: Most issues here are specific to blockchain development and the payout is in cryptocurrency.

- Bugcrowd

- HackerOne

- Bountysource

What to do first

Let’s assume that you found a project of your liking, here are some ways that you can find out if it is a smart idea to start working on that repository:

Proficient with the used programming language

No matter how great the project sounds, if you have no prior experience with the used programming language or tech stack, you will have a hard time fixing an issue.

Check the popularity of the project

I recommend going for a project that is not too popular yet - all the good issues would be gone too quickly - but also not so small that the chance is high that the project might become unmaintained at some point. Aiming for a star count on GitHub between 1000 and 50k is usually a good bet, but there are some exceptions.

Check the latest commit in the master branch

Don’t contribute to a repository if you see that there was no commit added to master for more than a couple of months, it can be a sign of a deserted project. When having doubts about the ongoing development of the project, ask some contributors or open up a new issue.

Take a look at the number of open pull requests

Are there a lot of open pull requests? If it is not a highly popular project, this can be a clear indicator that the repository cannot keep up and doesn’t have enough members for handling the reviews. Alternatively, it could also be that there are organizational issues that lead to slow decisions or the direction of the project is lacking.

Check for interesting issues to work on

Well-organized repositories usually have issue labels like “good first issue”, “help wanted” or “documentation”. These can be an optimal start to get to know the repository. When you find a suitable issue, make sure it is not taken by someone else yet. If it is an older issue, write a comment to find out if there is still demand for a solution to avoid working on an issue that is not wanted anymore or superseded by other changes.

Find contribution guidelines for the project

While you can always find out how to get a project up and running locally yourself, a good project usually has information for contributors in the README.md file or more specifically in a dedicated CONTRIBUTING.md file.

Preparations before working on a project

By now, you selected a project that fulfills all the criteria of being a good pick: it is continuously maintained, you found interesting open issues and you feel skilled enough to start the work!

(Optional) Make sure to add an SSH key to your GitHub account

With GitHub, you can clone a repository either with HTTPS or SSH. Various online discussions are going on between which way is better, I prefer and recommend SSH over HTTPS because you don’t have to re-enter your GitHub password every time you use operations like git push.

If you are unsure about how to generate an SSH key and put it into your GitHub account, here is a good article: Connecting to GitHub with SSH.

(Optional) Add a GPG key for verified commits

Although you can commit to a repository just fine without your commits being verified, I recommend setting up a GPG key for these three reasons:

- your commit will receive a green “Verified” label which gives it improved authenticity

- you show other people involved in the project that the commit comes from a trusted source

- others can be sure that no one impersonated your account

You can read more about generating a GPG key and verifying your commits here: Managing commit signature verification.

When you have your GPG key generated and set up in GitHub, it can be helpful to run these commands to tell git to auto-sign every commit:

git config --global user.signingkey <publickey>

git config --global commit.gpgsign trueReady to clone

Let’s say you want to contribute to React, then the command for copying the project to your local disk would look like this:

# ssh

git clone git@github.com:facebook/react.git

# https

git clone https://github.com/facebook/react.gitAfter the project is successfully cloned to your local disk, you can find the repository available under the file path that you were located in when cloning it.

Find the used branch for development

Before you start to work on the project and begin modifying files, it is a good idea to check the branches on the GitHub repo. Although most of the time you branch away from the master branch for your contributions, there are repositories that use a separate dev or development branch. These intermediate branches are used for pull requests and get merged back into master regularly when deciding on pushing out a new release.

Familiarize yourself with the project

Depending on the size of the project, it can be quite the challenge to figure out which files require a change for providing a bug fix/feature. Try to scan over the file structure once at least before using the search in your IDE for pinpointing the location for your code changes.

Don’t get discouraged!

Starting with a large project can be overwhelming at first. I often wanted to give up on issues already only to find the ideal solution a moment later. It can pay off to be perseverant.

Nevertheless, you will encounter projects - especially older ones - which can suffer from bad developer experience. When you realize that it will take you a lot of time to even get the project setup or the tests and linting to pass, focusing your work on another repository might be a better idea.

Get things done

At this point, you have familiarized yourself with the project and you are sure that you can make some meaningful code changes.

Reserve the issue of your choice

You can signal the contributors of the repository that you want to take an issue by simply writing “I want to work on this” as a comment. Ideally, you will get assigned to an issue and avoid that your issue will be taken by someone else.

Be aware that you are expected to deliver a PR or a status update once you volunteered for an issue. Some contributors also might ask about the progress if is a high priority bug fix.

Save work into a branch

Since we are still in the default branch that we cloned the project from, it’s about time to check out into a separate branch to be able to commit.

I recommend naming a branch according to the <issue-number>-<issue-name> naming convention.

An example of checking out into an issue-specific branch would look like this:

git checkout -b 345-expose-options-for-gtagIf you want to read up more on the topic, there is plenty of information available about Git branch naming conventions.

Ready to commit

We already learned that there are naming conventions for creating branches in Git, so we also want to follow the best practices for the structure of a commit message. Conventional Commits is a good resource of “a specification for adding human and machine-readable meaning to commit messages”.

Set up git commit default message

As programmers, we prefer to avoid unnecessary work and stick to the DRY principle. That’s why I advise using a git commit default message. Whenever I start a commit message, I can check which type of change I am working on and adapt the message and its body accordingly.

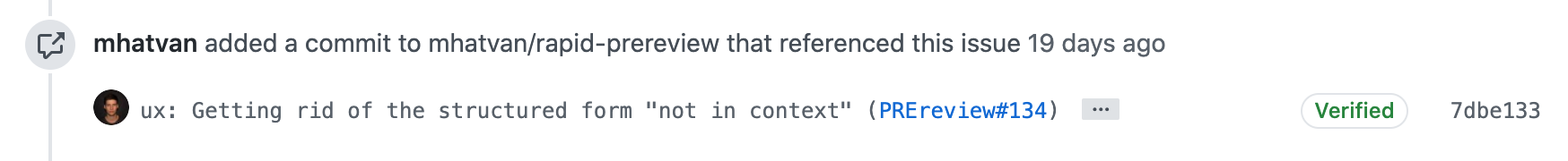

A useful hint: whenever you put the issue number into your commit message like (#<issue-number>), the respective issue on the remote repository will receive a timeline notification that looks like this:

Everyone interested in the issue will see that you started working on it.

This can be helpful especially for pull requests that span across a longer time frame to further signal to other subscribers of an issue that you are indeed working on it right now and that the pull request is not abandoned.

Check how commits are done in the repository of your choice

Although you are good to go most of the time with sticking to the conventional commit structure for commits, I advise running git log in a project where you contribute for the first time to see how strict commit messages are handled.

Make sure you comply with the outlined contribution guidelines

Before committing, double-check that you fulfill all the requirements of a potential CONTRIBUTING.md file. Whenever you add a new feature, it can be a requirement to add a corresponding unit test to the project to verify that your changes are reliably working or that you update the documentation to explain the feature.

Focus on the issue at hand exclusively

Don’t touch any code not related to the bug you are fixing or the feature you are implementing and stick to the code style of the project.

Sometimes, the pull request reviewers will also explicitly tell you to revert formatting or refactoring changes that you did out of goodwill. The main reason is to keep the pull request easy to read and review and to avoid time-consuming discussions about irrelevant changes in the code diff.

Squash commits

Do as many commits as you need while the pull request is in a work in progress state, but rewrite and squash your commits to result in one nice and clean commit in the end. This way you avoid polluting the master branch with excess information in git log.

In case you are unfamiliar with squashing commits, this beginner’s guide to squashing commits with git rebase can help you out.

Ready to push

If you’ve gotten this far, great! You’re almost ready to open your first PR! There are only a few steps left.

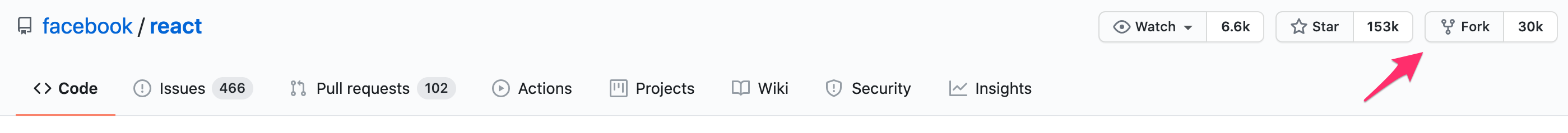

Fork repository

Forking is just a fancy word for taking a repository on GitHub and copying it under your own GitHub username. It can be done by clicking the Fork button on the right upper corner on any repository as can be seen here:

The fork button is in the upper right corner in the GitHub UI.

The reason why we need to fork a repository is to be able to submit a pull request against it. By default, you don’t have push permissions to a repository that doesn’t belong to you. Therefore, we fork a repository under our username where we are allowed to push to, and then we can submit a PR against the original GitHub repository.

So if you would decide to fork React, it would take a few seconds, and then you would have an exact copy of the repository available under https://github.com/<username>/react.

Although the step of forking can be done earlier in the workflow, at this point we already made a git commit previously, so we know for sure that we have a meaningful contribution to push. If you fork a repository before checking out the project locally and finding out if you can do valuable changes, it can be that you decide against working on it and then you forked it in vain.

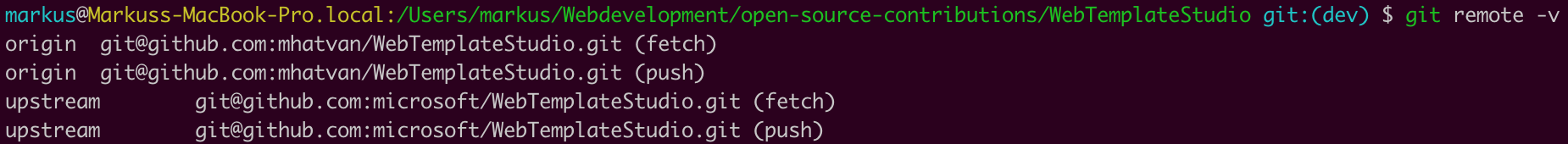

Set up a git remote

When you clone a repository from GitHub to your local disk, it has the origin set up for you.

If you run git remote -v inside the location where you cloned the repository to, it should look similar to this: origin git@github.com:facebook/react.git.

When you run git push it will try to push against origin which would not work in this case since we are not a member of the Facebook group.

We need to change the origin to be our fork and the upstream repository to be facebook/react.

To do that, we can run:

# add facebook/react as upstream

git remote add upstream git@github.com:facebook/react.git

# change origin url to be <username>/react

git remote set-url origin git@github.com:<username>/react.gitIf you did everything correctly, the output of git remote -v should display origin and upstream set up:

Output of git remote -v.

Does it look similar like in the screenshot above? Good job!

Push to origin

The remaining steps should be fairly easy. We push our branch with the squashed commits that we made to the origin, which is our fork.

The command to do that is:

git push origin <branch-name>Super, we are almost through!

Ready to open a PR

If you did everything correctly, you will be presented with an alert box at the location of your forked repository, notifying you of your recent push.

After you are 100% done with your work, click the “Compare & pull request” button.

Write a useful pull request description

To make the review for the maintainers of the repository as easy as possible, we should follow the best practices for a good pull request description.

This is the minimum that I would put there:

Closes #<issue-number>.

<explanation>GitHub will parse the “Closes” keyword and automatically close the issue when the PR gets merged.

The <explanation> part can be very different depending on your contribution. It might be that you want to explain the bug that you fixed, notify about potential problems that could show up in the future, or discuss breaking changes that your PR might lead to.

Additionally, some repositories might have dedicated pull request templates set up. Then you would need to check checkboxes making sure that e.g. linting goes through without errors, you added unit test cases for your new feature, no formatting changes were committed, depending on the repository.

When you are content with your pull request description, the only thing left to do is to click that rewarding, green “Create pull request” button and voilà!

Wait for approval

Depending on the project, this can happen quickly or take a while. Sometimes you will have to do multiple iterations of improvements for a pull request, other times your work will be merged right away.

That’s all folks!

You successfully created your first pull request!

Thank you for wanting to give back to the open source community, a lot of projects can only thrive with support from people like you!

I know this was a lot to digest, but you should have all the necessary steps laid out to go from zero to hero.

I hope this article has been helpful to you, let me know if there are any open questions left or passages to add.

Thank you for reading!

Helpful resources

- Open-source guide

- How to contribute to open source projects

- How to make your first open source contribution in just 5 minutes

- Your first open source contribution: a step-by-step technical guide

- 5 reasons why you should contribute to open source projects